SC Wine Chronicles: Rethinking AVA Boundaries

By Dan Berger

Today’s Article Summary: Wine journalist Dan Berger explores how American Viticultural Area boundaries, shaped by past conditions and assumptions, may no longer align with today’s realities. Using Sonoma County’s Russian River Valley as a case study, he considers the impacts of climate shifts, changing grape varieties and evolving farming practices. Berger invites a broader conversation about whether AVA boundaries should adapt as the landscape of wine production continues to change.

SONOMA COUNTY, Calif. — Redistricting has become an important political buzzword recently with lots of people becoming exercised over the issue. It basically speaks about where the boundary lines should be that separate political districts that are theoretically considered to be fair and represent a true picture of voting conditions that are equitable.

California’s Prop. 50 had greater political overtones than in normal ballot issues, and because it was controversial it raised debatable points that required the ballot box to resolve.

No such controversy exists when we speak about the boundaries set up to define named areas throughout the United States for the U.S. wine industry. Few people dispute the locations of boundaries for the Napa Valley, Sonoma County, Mendocino Ridge, Paso Robles and dozens of other American Viticultural Areas. Many have been with us for decades, and regular wine-consumers generally understand where they are and what they represent.

But many people who work in this business of making wine have implied to me, in private conversations not meant for public consumption, that there is a time sensitivity to several important California AVA regions that have boundaries that were, in their view, questionable at best when they were established and today are downright ridiculous. Some of the AVAs were established so long ago that things have changed or the original boundaries were incorrect.

General laws may be viewed in this way also. Some bills were written and passed into law at a time when they solved a problem that existed then. But since that time, such laws have become obsolete and might not apply to anyone. Any laws that are still on the books that pertain to mustache wax, treatment of hansom-cab horses, corsets, typewriters and high-button shoes may still be there only because they were never repealed.

Some of these ancient laws may have been written without clauses, known as “sunset provisions,” in which a time limit is specified when the regulation is made invalid or the legal body that created the law is able to reevaluate its importance or current validity.

“Should American AVAs have different boundaries for different grape varieties?” — Dan Berger

The Encyclopedia Britannica says that numerous sunset laws were widely used in the 1970s “to eliminate bloated and unresponsive government bureaucracies.” Occasionally laws were written to control programs that “served only a few special interests” and which some legislatures knew should eventually be either repealed or rewritten.

I believe several, perhaps many, U.S. AVAs or sub-regions’ boundaries today are candidates for reevaluation because they represent conditions that existed in the past and now have changed. I can think of several justifications for making changes in existing sub-AVAs.

Climate change: This is the most obvious change in how wine is made today in comparison with how it was made 30 or 40 years ago. Not every region has seen a radical increase in its overall climate. But climate change has occurred so consistently over the decades that farming has had to adapt to conditions that previously never existed. Some areas that once were appropriate to be in a specific AVA today should be removed from it.

New grapes: One aspect of the original justification for an AVA is that it did extremely well with certain grape varieties while others were never considered because they didn’t exist in that same area. But as time has evolved, we now see a rebirth in chenin blanc and greater interest in albariño, vermentino and grüner veltliner, and the old boundaries may not be appropriate with the new varieties. Some AVAs should be expanded or contracted because new varieties require it.

Technology: Grape and wine expertise has exploded in the last four decades, giving growers new tools (fertilizers, farming systems, trellising designs, irrigation theories) that allow for significantly more interesting wines that might well expand a smaller AVA into a larger one.

It seems clear that there are enormous differences between California’s AVA system and the old French appellation d’origine contrôlée, which often were compared and seen by some people as parallel systems.

When the United States began approving AVAs for the wine industry in 1980, it was alleged by most AVA supporters that the two systems did the same things. Both were designed to define specific regions that had their own unique characteristics, and the consumer could be confident of buying a wine that the French would say had typicité.

But in today’s world two major things have changed radically since 1980. One huge change in the systems: In the French AOC system the government dictates not only which specific grape varieties may be planted in a region but how much fruit can grow in a vineyard. Americans are free to plant any grapes anywhere they choose, and they can grow as much fruit as they want.

France has a sotto voce agreement with people inside the wine industry about what would be appropriate production levels for each region if quality is to be maintained. The U.S. government has no interest in making any kind of accord with anyone in the U.S. wine business. Indeed, in some ways the two sides see each other as adversaries. (I expect to get push-back on this belief.)

The second issue that has distorted the French notion of typicité here is simply that France has a European (cool, continental) climate that mitigates against high alcohols. Almost all of France’s better-known wines from named districts and even most of the lesser-known ones established the styles that have become standardized and have been adopted around the world by others.

Challenge your vocabulary with this week’s mystery word. Submit your answer in the poll, and check the bottom of the page for the correct answer.

This means that most French table wines typically have between low alcohols (12% to 13%), and at that weight typicité is much easier to achieve. However, California’s Mediterranean climate is far more conducive to producing wines of much higher alcohols, which then are more difficult to achieve replicable regional characteristics.

Also, domestic buyers’ obdurate demand for soft, sweet, higher-alcohol products have strongly encouraged wineries to deliver massive, lower-acid wines. The majority of California wines have at least 14% alcohol, and some of the most expensive are much higher. Much.

This essentially means that typicité is either subjugated or demolished, which in terms of an AOC/AVA comparison means that Americans simply don’t care about typicité or authenticity as long as they can have their soft, sweet, rich wines. And AVAs may actually, in some cases, prove to be detrimental in certain varieties of grapes that have recently become popular.

A case in point would be syrah. Unless it is grown in a specific way in a warmer climate, it can be difficult to achieve any sort of varietal precision. But when it is grown in a cooler climate, which is far riskier, the resulting wine can often be some of the most dramatic and varietally fascinating in the world.

Which leads me to the inevitable question: Should American AVAs have different boundaries for different grape varieties? And if so, what sort of expert hierarchy could make such a determination? It’s an interesting question that could lead to some fascinating discussions.

My argument about revisiting older AVAs through the use of sunset laws requires at least one example. Since I live on the eastern outskirts of the Russian River Valley and know a lot of winemakers who ply their trade in the region, the question comes up often: Are the RRV’s current boundaries correct?

It’s hard to estimate how many RRV winemakers think the present RRV boundaries are perfectly fine as they are. But if I had to take a wild guess, I’d say those who think this way number about two. I am not naming names.

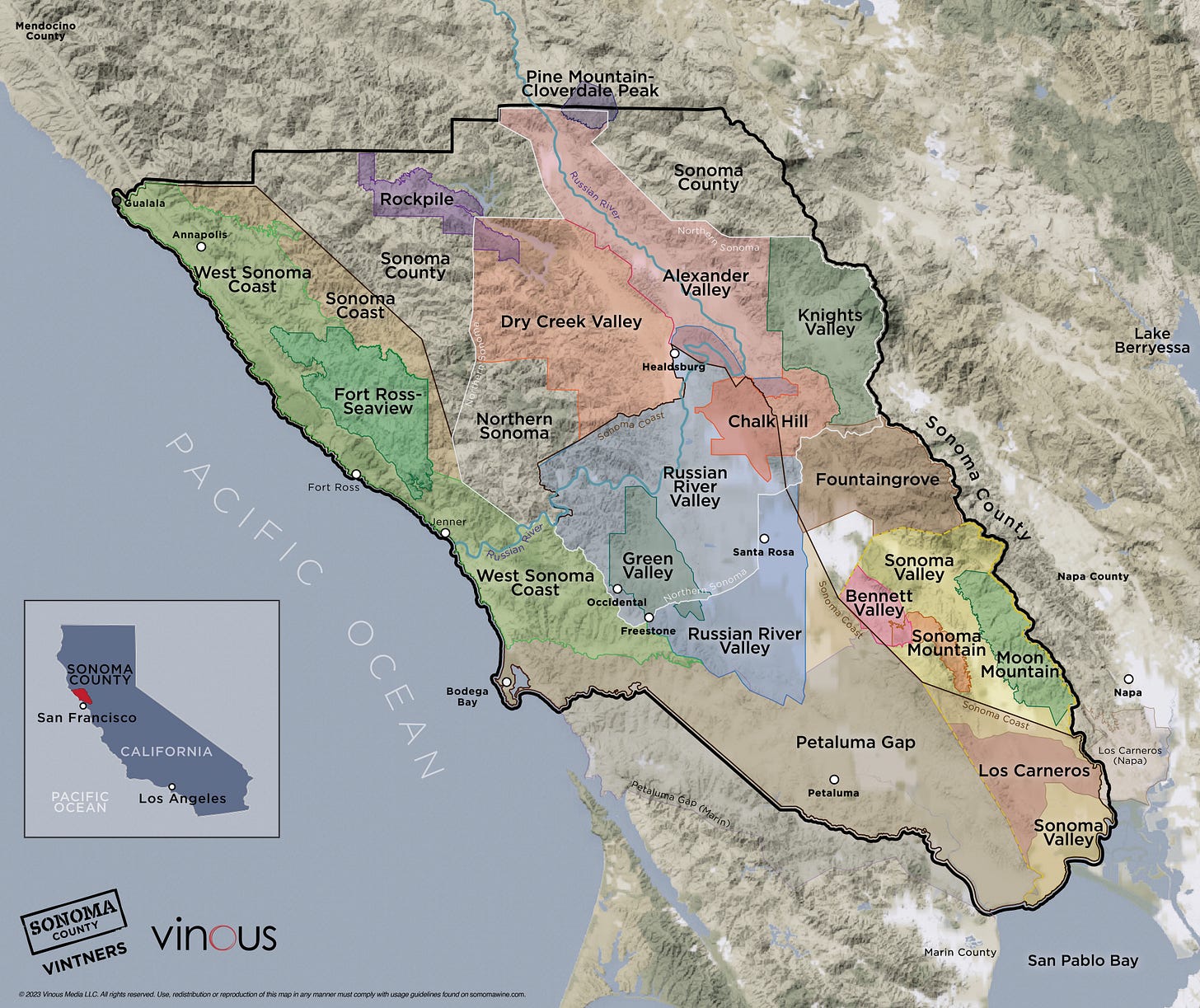

The original boundaries of the Russian River Valley, based primarily on fog intrusion and morning dissipation in the area, were approved in 1983. RRV is between Sebastopol and Santa Rosa in the south and from Forestville to Healdsburg in the north. The area was, in 1983, generally considered to be universally cool. Fog marked the boundaries. Somewhat controversially, the AVA was expanded in 2005. Some people are still upset about that.

Back in the day, the region was so cool that parts of the southern tip of Russian River Valley near the Pacific Ocean were so cold almost nobody would risk planting grapes. It was often said that grapes would ripen only seven years out of 10 and that in the other three years growers faced either disaster or an extremely small profit.

As time has passed (42 years!), improved farming methods, conversion of some grapes (ripping out some grapes to increase plantings of pinot noir) and better irrigation systems have aided the region in gaining a greater national and worldwide reputation for quality chardonnay and pinot. Indeed, the AVA now offers some of the most respected vineyard-designated pinot noirs in the state.

When I think of the district, however, I also think of how the success of pinot noir has also meant the near complete destruction of some of the finest wines California ever made. Phenomenal riesling, gewürztraminer, zinfandel, cabernet sauvignon and grenache once flourished here. But the quest to make quality pinot noir and chardonnay prompted the removal of some of the finest vines in the world.

(It’s true that sauvignon blanc and barbera, to name just two, continue to make fabulous wine from this wonderful AVA. And I believe that if economics made it possible, syrah could make a phenomenal wine here.)

Moreover, there are probably five or six sub-districts within Russian River Valley that could well be redefined as sub-sub-districts and two or three more areas that should be removed from RRV that are now too warm to truly still be defined as cool-climate areas. (One RRV area to the north is considered by some locals to be the best cabernet land in the county.)

This entire subject of AVA boundaries was one that was of interest to the people who founded Appellation America several decades ago. Its website contained dozens of stories about regional characteristics for wines across the United States and included wineries in New Jersey, Virginia, Missouri, Idaho and, of course, throughout California.

Unfortunately, the trove of data collected by various contributors to the site could occasionally be a little geeky, and after several years of trying to make the site commercially viable, it eventually closed down due to lack of funding. But people behind the project continue to hold out hope that some of this material could be resurrected. It is vital to the industry.

Even if sunset provisions are not going to change any existing boundaries, I have spoken with several people who continue to be regional cage-rattlers and who would love to reopen the discussion about a few regions to set the record straight or make adjustments to correct what has changed over the years.

The sad fact is, however, that unless a dynamic individual who cares about this subject of regional typicité makes a strong and vocal case that existing boundaries should be regularly rewritten, chances are rather strong that we will be left with these outdated boundary lines for decades, long after they have outlived their usefulness.

—

Dan Berger has been writing about wine since 1975.

Editor’s Note: Wine Chronicles is a series from Sonoma County Features that explores timely, nuanced topics affecting the local world of wine, often written by longtime journalist and wine critic Dan Berger.

Today’s Wine Discovery

2024 Balletto Gewürztraminer ($25) — Grown and made by the Balletto family in Sonoma’s Russian River Valley, this dry white revives a variety once widely planted in the region. Estate grown and bottled, it is fermented in neutral oak with no residual sugar. The fruit comes from Goldridge soils and Gewürztraminer Clone 1.

Aromas of lychee and golden apple lead, followed by orange blossom. On the palate, rose, ginger and nutmeg show through. It’s medium-bodied with unexpected weight and texture, balanced by 13.9% alcohol, a pH of 3.48 and 5.5 g/L of acidity. Subtle tannins from the thick skins help extend the finish.

Pair with pork and ginger dumplings, roast duck with five-spice or shrimp and mango salad. Also works well with Thanksgiving classics — turkey, cranberry sauce and sweet potatoes — Tim Carl Review

Today’s Polls:

This Week’s Word Challenge Reveal:

The correct answer is C: “In terminal decline.”

“Moribund” describes something that is stagnant, outdated or approaching failure —whether it’s a tradition, institution or system. In the context of AVA boundaries, it applies to designations that no longer reflect current climate conditions, grape varieties or farming practices. When rules don’t evolve with reality, they risk becoming irrelevant, even obstructive.

The word comes from the Latin moribundus, meaning “dying,” and entered English in the early 1700s. Once used mainly in medicine, it now applies more broadly to describe social or structural decay. It is a useful term in any conversation about reforming legacy systems — especially when those systems resist change.

Explore These Related Articles:

Browse All Sonoma County Features Stories

or explore…

All Napa Valley Features Stories

The views, opinions and data presented in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy, position or perspective of Napa Valley Features or its editorial team. Any content provided by our authors is their own and is not intended to malign any group, organization, company or individual.